Squad

Before touching this subject, let’s make it clear I’ve nothing against the name Squad. When the company is undergoing an organizational transformation, there will be moments in which we’ll want to highlight a break from the status quo. Changing titles can be a good way of doing this. The problem is how companies have been using this title.

History time! In 2014, Henrik Kniberg presented how some development teams worked in Spotify (music stream services – check out the original articles here and here). Many companies liked the idea and began to adopt the Spotify “model”. I put that in quotes since, in 2015, Henry himself said there’s no such thing as a Spotify model (watch this, around minute 45-ish).

In the original articles, he tells about how they worked before, and the years of experimentation they’ve gone through to get to where they were then.

It didn’t stop several companies from ignoring the “years of experimentation” part, all the fails, and successes and begin to “implement” such a “model”. Overnight the names of teams, business units, or departments became Squads. Like magic, by calling a group of people a Squad, all problems are solved, and we suddenly become agile! How? I don’t know. A wizard did it!

But nope. That’s not how it works. A group of people incapable of building a product end to end remains that way, no matter the name. To create a real multidisciplinary team, we need firm action, clear goals, and lots and lots of work.

John, the undying specialist

For decades the tech industry got used to having ultra-specialists in certain subjects. And when we build a development team, we often keep this high specialization structure within that team.

I’ll give you an example and call our specialist John. Maybe you’ll identify yourself with him, or perhaps you know someone a bit like our character.

The team is in John’s hands. The specialist’s hands. If he’s there, everything works; if he’s not, it doesn’t. At first, John is happy. After all, he’s the hero of his team.

But it’s not all sunshine in John’s life. On his way to that long dreamt tropical vacation, his phone rings. His team has a “small problem” that requires John to clarify some details… for 2 hours. John lands in Miami, turn the Wi-Fi on, and gets 265 messages he has to answer since the team depends on him. Waiting for his flight to the Bahamas, he answers them all. Once in the Bahamas, he turns the Wi-Fi on once again to get the GPS to plot the way to his hotel for that night… and he has 367 new messages because when trying to fix that “small problem” the team has created a new huge one.

John tries to answer everything, but then his boss calls. “John, you’ve got your notebook, right? Log in here a sec and generate that XYZ Report ’cause people here don’t know how to.” Desperate, John scrambles for his notebook in the chaos of check-out and getting a car.

John’s wife sees him opening his notebook and gives him THAT look. His younger son is throwing up at the feet of an old lady who screams words John can’t understand, and his elder daughter is almost leaving the lobby. John knows his vacation is over before it even starts.

Total panic ensues. John shouts at his boss to stay in the lobby, says, “Lo siento.” to his other daughter, delivers the report to his wife, and doesn’t even remember he has a son. John has a heart attack and dies.

The company, however, cannot stop, and John is crucial. Nowadays, there are regular Ouija sessions every day at 11:00 to consult with John, who cannot rest even after death.

Jokes apart, excessive specialization has severe consequences to the development team. The first is the specialist’s dependency, and the second is low efficiency since the ultra-specialist will inevitably become the team’s bottleneck.

The situation is even worse if the team is segmented in several specialists. In the same company above, Jane, Jill, and Jack are in a team in which each one of them only did their thing, and nobody knew how to do the other’s job.

A way to reduce this dependency is to abandon specialist silo. Working in pairs, Dojos, inside training, and workshops are some of many forms of turning type I professionals (specialists) into type T professionals (generalist specialists).

Teams of specialists

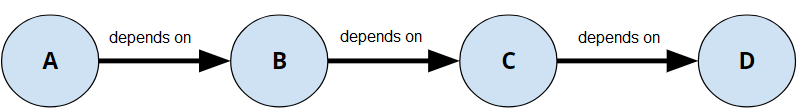

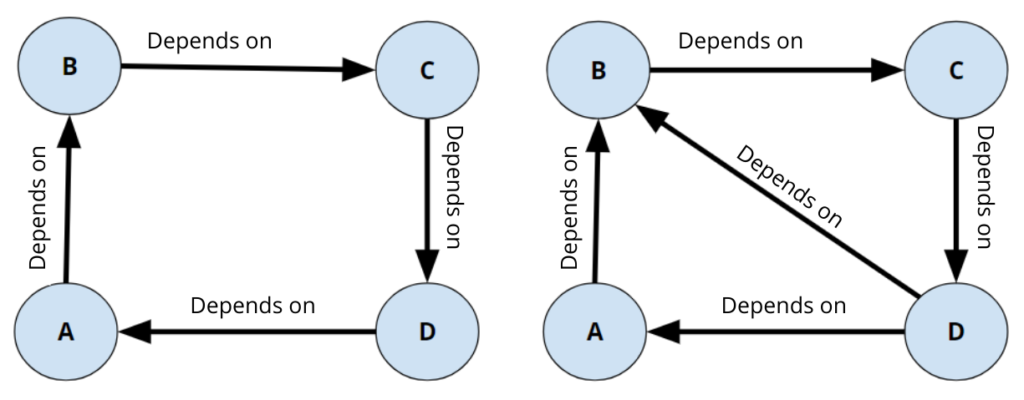

Having a hyper-specialist on the team is terrible, but having teams made entirely of specialists in a given field of knowledge is just as counterproductive. For example, Team A is responsible for a specific delivery. But Team A depends on Team B for that. They may not know, though, that Team B depends on Team C, which in turn depends on Team D, and so on.

Common examples in software development: UX Team, Front-End Team, Back-end Team, Database Team, Production Team, Business Team…

Nobody is responsible for delivering the product. Each great silo is responsible for a tiny fraction of it all and “throw the ball” to the next in line. Suppose you thought of an assembly line made of furiously typing human machines, bingo. What could go wrong?

And this issue only escalates with circular dependencies.

The solution to these lies in the creation of multidisciplinary teams. The less handoffs you have, the more efficient the team will be.

I’ve done my part already

When we adopt Scrum, there’s the role of Product Owner. However, it’s also necessary that the whole development team has a sense of product ownership. There’s a huge difference between when you own something and when you don’t.

Imagine there’s a leak in your kitchen ceiling. You’ll probably not stay there watching it getting worse. It’s your apartment, after all, so you’ll take good care of it and solve the problem immediately.

Now picture a situation when you pay a visit to a friend and notice there’s a leak in his kitchen ceiling. What do you do? Alert them about it? Tell them you know someone who could help? Stay quiet, since you don’t want to intrude?

Notice how in the first case, in your own home, you do something to solve the problem: you fix the leak, or you call in someone who can. When it’s not your kitchen, though, the most you do is talking about the problem, but solving it is another’s responsibility.

The same happens when we talk about products and services in our companies. If we feel like we own the product, we grow attached to it, and we want it to be the best product in the world, useful, enjoyable, pretty, safe, etc. When we lack this feeling of ownership, each of us will strictly do their part, and any problem not directly related to it will always be someone else’s business.

To create this sense of ownership, two things are essential: the first one lies once again in multidisciplinary teams. And the second one comes from Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP): do not reinforce negative statements about the product. For example:

- This product keeps crashing.

- Yep. Remember the Great Server Crash of 1998?

- Woah. A week sleeping in the office. That was hell…

- It would be better to just throw it all away and restart from scratch, really.

It may look silly, but it’s quite pernicious. It creates a hostile environment in which each team member reinforces negative aspects of their work and builds a stigma to the product. Let’s try substituting complaints for actions.

- This product keeps crashing.

- What happened? How can we solve it? May I help?

Taskers

There’s a considerable gap in efficacy and efficiency when comparing teams focused on delivering value and tasker teams. Andressa Chiara has well explored this theme in the article The Tasker Team and the Product Team, so I’ll just summarise it here.

In agile methods, we want to deliver the product in an iterative and incremental way, with the highest value delivered in the first iterations. Thus, the most essential items are always at the top of the backlog. Suppose the team is working on the top priority item, and then something happens. The team cannot proceed with that item. What’s the difference in the response of both teams?

Team focused on delivering value: We have to remove these impediments since this is our most important item to deliver. There’s nothing in the backlog that’s more important than this.

Tasker team: Mmm. Let’s do another item. This one is blocked.

Unfortunately, there won’t be just one obstacle to a team’s work, and the number of unfinished items in the backlog of a tasker team will be huge.

A single tasker can also be a problem even without any obstruction. For example, if I have a specialist in my team and his role in the value item is small, he’ll tend to try to finish tasks “in advance”. He’ll be on item number 5,778, while the rest of the team would still be on item 4. This “advancement” is an illusion, though, and it’s quite probable that he’ll have to rework those 5,774 items. Having lots of unfinished items means you’re overstocked, and as with any overstock, it’ll deteriorate with time. Changes in the market, previous results, changes in the customer profile, etc.… Anything can (and often will) happen, and reworked items have a higher chance of mismatch with real-time project needs.

We’ve got no time to…

“Here we work, we work, and then we work some more. There’s no time for anything else.”

(Ernest, 22 years old)

That’s usually a natural consequence for the tasker team. We have no time to plan, improve, study new technologies, and think about different solutions. It’s just work, then work, then work some more to deliver those tasks.

In the beginning, working excessively on a project, product, or service seems like a good idea, but with time it does become quite a burden.

For the team to improve its way of working, innovating, and learning, it’s necessary to include some spare time, time off in the flux of value. If you want to know more, check out Want to enhance your company’s productivity? Give’em some time off!

So…

Dysfunctions are quite common in development teams, but we must not accept them passively. It’s everybody’s responsibility to fix them, from the team and the Product Owner to Scrum Masters and managers.

I hope you enjoyed this article. We’ll be back soon with Dysfunctions of a development team – Part II.

Want to know more about Scrum roles? Consider yourself invited to our Certified Scrum Master (CSM).