Many organizations are facing difficulties during their Agile transformation in search of Business Agility. The plan was clear, well designed, and management was on board; teams are now called Squads, and the Agile framework or method has already been chosen and implemented with reasonable success in IT. However, months have passed, and results have not yet come as expected, creating pressure and discomfort on teams and management.

This scenario, which is very common in organizations around the world, reveals many problems and misconceptions that are often missed by organizations, which eventually blame the method. The trauma can even make them return to their previous state, giving up the transformation process. In other cases, the problems are simply ignored, and the final stage of the transformation process is “we have agile teams” while the result for the organization’s business is marginal.

One of the causes of this type of problem is often the focus on local optimization, that is, seeing a team as an island, or encouraging, often unintentionally, team improvement in isolation from the rest of the organization. Teams then promote their local optimizations without looking at the organizational system as a whole. In this case, the “organizational system” is defined as the relationship and dependency between the parts of this organization. In a scenario where, for example, one team builds, another validates, other documents, and another delivers, even if all of these teams are agile, system improvement will not necessarily occur as teams look only at their internal processes, ignoring the flow of the value chain as a whole and the dependencies and relationships between them.

This is where the Flight Levels come to light: a model for thinking about communication and alignment of the organization to get the right team to develop the right product at the right time, promoting improvements at different levels of the organization, and generating real optimization in the value stream.

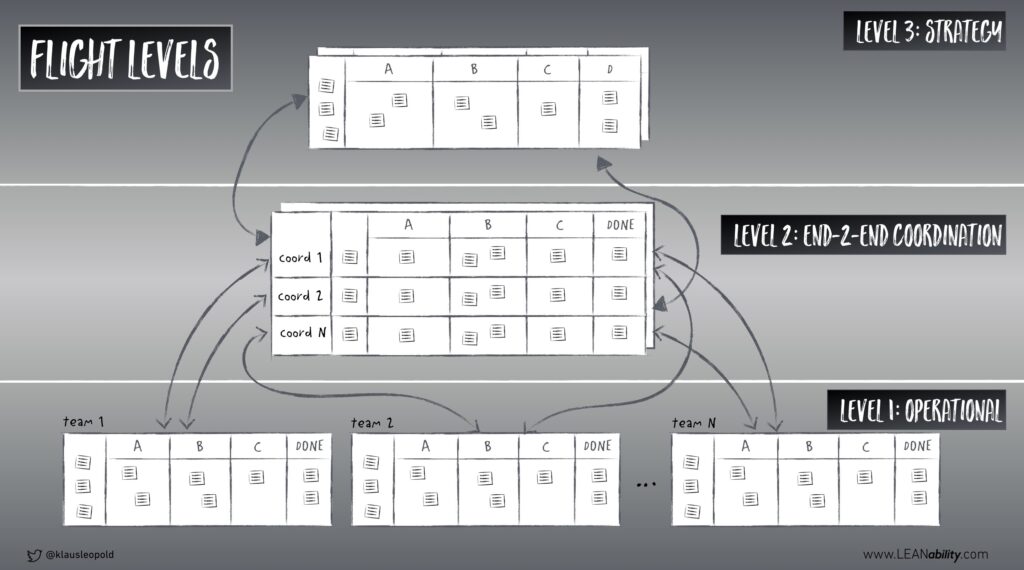

The Flight Levels model has 3 levels, described below:

- Flight Level 1: the lowest flight level, looking at the operation, focusing on the product and/or service development team. Level 1 teams perform 4 key activities: view their work, limit WIP, routinely seek and integrate feedback, and promote identified local improvements.

- Flight Level 2: a slightly higher level of flight, looking at coordination between parts of the organization, focusing on collaboration, communication, and coordination between teams acting at different stages of the end-to-end value chain. In level 2, the same 4 activities of level 1 are performed, maintaining the communication between the two levels. It is at this level that portfolio management emerges, and this is where team dependencies are identified and addressed, generating visibility, drawing attention to bottlenecks and team synchronization.

- Flight Level 3: the highest flight level, focusing on aligning the prioritization of initiatives (projects and products) with the strategic direction of the organization. Here strategic management is connected to the operation. At this flight level, the C-Level also becomes Agile, and the progress of strategic objectives is monitored.

The Flight Levels model focuses on continuous value chain optimization, rather than local optimization of each team, where understanding the context of the organization is fundamental, designing a flight level architecture to enable end-to-end flow visualization and management and understand the best follow-up meeting metrics and cadences for each flight level.

Although the model is simple, there are many elements to consider. While management involvement and commitment is challenging, using this thinking model leads to significant and profound cultural change, with incredible mid- and long-term results leading the company to truly apply the much desired Business Agility.

If you want to know more about Flight Levels training, check out here!

This article was written by Marcos Garrido, Lula Rodrigues, and Jose JR.