The PO starts the Planning and shows the team a list of stories he has prioritized in the product’s backlog. The first item is to create a screen where the user can enter his or her personal information. The team asks about the mask and format for each field, whether the information needs to be consulted anywhere, and whether the layout is ready. Some developers complain that the details aren’t clearly described in the story, and the PO can make adjustments. The team evaluates 8 points. We can move on to the next story in the backlog.

How many problems can you find in this situation? If you’re used to working with a task team, perhaps you won’t see any. But there’s much room for improvement here, with a few dysfunctions which can cause real disasters in a product.

A task team is one which focuses entirely on the list of tasks to be executed. It can even be in the habit of creating technical stories, often by surprise during planning, because “it’s important”. This is a team which values efficiency over efficacy because it’s more concerned with throughput and speed than with what is being delivered of value to the product. This team delegates exclusively to the PO the command, understanding, and decision-making about what will or won’t solve the consumer’s problem. The hypotheses for a solution to a problem are left to the PO and, with luck, the designer. The team’s job is merely to make technically viable whatever the PO has decided is to be done.

We talk a lot about the agile mindset, but when you come across a task team, this mindset seems to vanish the minute they realize they’ll to have to burn some grey matter thinking about how to resolve the user’s problem. This team fails to recognize that the best solutions emerge from multi-disciplinary teams (no, the PO is not a multi-disciplinary team) and that solving a really important problem will require all the team’s minds to think together. Instead of embracing this attitude, what we see is a shift of responsibility and cognitive effort to the PO. Meanwhile, the development team members – often including the designers – take an attitude of “I’m just obeying orders”, “I’m a developer, I’m not paid for this”, “I need a comprehensive story scope”, “that’s what the PO requested”.

The result is a poor product with a reduced likelihood of success.

So how can we deal with these dysfunctions and turn a task team into a product team?

Problems, not solutions

In creating a story, we should avoid defining the solution. Take it to the team and talk to them using the 3 Cs suggested by Ron Jeffries: card, conversation, confirmation. Remember the objective of the story is to start a conversation, not be prescriptive. We use user stories so the team is able to empathize with the product’s consumer and help solve the problem, so explore this fully with the team and really go into the users’ experiences and frustrations. The team should be capable of answering the question “How does the product I’m developing help people?”, expressing its purpose without the slightest hesitation.

Refinements

For more experienced POs this may be old news, but it’s not unusual to find teams not doing Refinement. And these same teams usually have very extensive and exhausting Planning.

Refinement is a moment which occurs during the period of the sprint, looking at the items on the top of the backlog which will probably be absorbed by the development team in the next sprint.

The objective of the process of refinement is to get the stories prepared according to the definition of ready. However, it is possible that during Refinement the team discovers that it doesn’t have all the information to define what will be the solution for that story. And that’s great!

Imagine if one were to leave this to be found out in Planning?

During Refinement the team is expected to go over a few of the stories at a time. The attempt includes all stories which will be part of the next Planning can result in a very tiring meeting, so it’s worth thinking about short meetings for debate, recurring throughout the sprint. Examples: for two-week sprints, a 1h refinement per week. For one week sprints, two 30 min refinements a week.

It’s important that during Refinement the team:

- check that everyone understands the problem to be solved, the value to be given the product, the hypothesis test to be made and the reasons contributing to the prioritization of that story;

- help complement the story information, making it richer;

- discuss the solution for each item of the backlog, arriving at a consensus;

- identify whether it is necessary to involve more people to discuss the solution, and invite these people to the next Refinement;

- check whether there are still impediments or additional information to be collected – and deal with these as soon as possible, to complete the story’s preparation;

- gauge the story in relation to effort, since it’ll be used as the PO’s prioritization criteria.

However, the Refinement shouldn’t be used to break up tasks or do POC’s. Nor should it be considered a separate sprint task, since it only dilutes (during the sprint) a discussion which, if not done, will have to occur in a worse form during Planning.

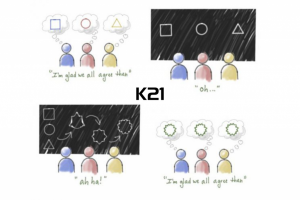

Dynamics of consensus

This is an excellent way of breaking the team’s expectation of receiving a pre-defined scope from the PO. Using dynamics of consensus, you can present a problem and temporarily omit the solution that you’ve thought of, while the team looks for alternative forms you may not have considered. This will enrich the hypotheses of your product’s solution and give the team the feeling it also belongs to them.

Regardless of whether you manage to refine your backlog with the exclusive participation of your team, or whether you need the presence of more people (other teams, consultants, stakeholders), it’s important to be aware that we’re trying to empower the team to solve a problem. This will require a balance between people whose posture is one of greater leadership (whether by nature or position) and those who don’t feel so comfortable manning the boat’s tiller.

Furthermore, apparent agreement demands special care. Questions like ” have everyone understood?” don’t help, because we have a tendency to always think we’ve understood, and that everyone shares our same vision. Have everyone write what each one has understood on a post-it and then compare the answers and reach a consensus, before writing the result on the board. That will make all the difference.

(PATTON, Jeff)

(PATTON, Jeff)Dual-track scrum

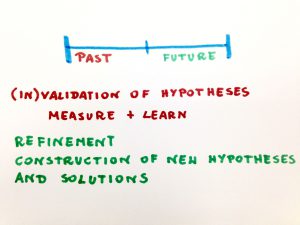

The objective of the concept created by Jeff Patton is to bring clarity to the product’s continuous discovery process. Part of the team is focused on developing items in the backlog which were already prepared and were part of the planning, with the PO, the UX and a member of the development team “discovering” what should be built next, making prototypes and validating hypotheses, which will generate prepared backlog items for the next sprint.

Let’s try one adaptation to explain the idea in a simple, practical way:

This is a “common” sprint versus a sprint in a dual-track scrum:

This is the content covered in a discovery track:

Mindset

Finally, it is necessary we always continue to demand the right mindset from the team. Without healthy peer pressure, there is a tendency for the team to sink into a comfortable, task-based posture, however much they’ve seen how pleasurable and motivational it is to be passionate about the problem and be part of the solution. After all, we’re fighting decades of conditioning focused on the faster execution of more things, rather than the search for the right thing to build.

Did you enjoy the article?

Learn more on our blog

Or simply join us on our Training